F-86 Sabre Jet

North American's jet, Flown by USAF in Korea

By Stephen Sherman, Sept. 2002. Updated January 23, 2012.

Bud Mahurin on the F-86, an Interview with SECRETS OF WAR

Q: This is Bud Mahurin and the title is "Korea: the Air War." What kind of aircraft were being used in Koera, and how did you find them?

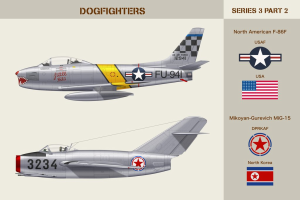

Mahurin: We were assigned F-86 Sabre jets, manufactured by North American Aviation Corporation. There were two wings that were involved. The 51st FIW at Suwon (airbase K-13) and the 4th FIW at Kimpo (K-14) near Seoul. Both wings were sent to combat the MiG-15, which had appeared in the skies over Korea. The MiG-15 was superior to the conventional straight-winged aircraft that we were then flying.

The F-86s proved to be a worthy adversary for the MiG-15s; they were our finest fighters at the time.

Q: Compare a MiG-15 to an F-86.

Mahurin: The MiG and the F-86 were fairly similar, both in appearance and performance. A lot of their development came from the scientific endeavors that the Germans conducted during World War II: jet engine development and the ability of a swept-wing aircraft to fly faster than a straight wing. We needed to fly longer distances than we’d been flying. Our objective was to keep the Manchuria-based MiG-15s from coming down into South Korea, and supporting the Chinese and the North Korean ground forces.

Q: What is different about the F-86? Compare it to a conventional straight wing aircraft.

Mahurin: Up until the development of the F-86, all straight wing aircraft were limited in their ability to approach the speed of sound. Based on German research during WWII, the swept wing came along; it presented a thinner wing to the air that it flew through. Thus it could go faster without compressing the air in front of the aircraft. This was a revolutionary development, it made a lot of straight wing aircraft that were being built obsolete. This established the trend for swept wings, which became the norm later on. One of the major differences between this aircraft and the MiG-15 was that the horizontal stabilizer on the MiG-15 was mounted above the vertical stabilizer. When the MiG-15 got into a spin, the air flying off the main wings would blanket out the horizontal stabilizer and the pilot couldn’t recover. They were ordered to bail out if they got into a flat spin. The low stabilizer on the F-86 meant that we could outperform the MiG-15s in various combat maneuvers, especially turns, and so it offered an advantage over the MiG-15.

Q: What were the MiG’s advantages over the F-86s?

Mahurin: Because the MiG-15 was lighter than an F-86 it could climb a little faster. While its forward speed during the climb wasn’t quite as great as an F-86, it could still climb at a higher angle of attack, and so, it appeared to us that the MiG could really climb. And, because of its lightness, the MiG-15 could reach a higher altitude than the F-86, high enough so that we couldn’t reach them, up above 45,000 feet.

Specifications (F-86A):

Armament: Six .50-cal. machine guns and eight 5-in. rockets or 2,000 lbs. of bombs

Engine: One General Electric J47 turbojet of 5,200 lbs. thrust

Maximum speed: 685 mph

Cruising speed: 540 mph

Range: 1,200 miles

Combat ceiling: 49,000 ft.

Span: 37 ft. 1 in.

Length: 37 ft. 6 in.

Height: 14 ft. 8 in.

Weight: 13,791 lbs. loaded

Crew: One

Q: This was the first war in which jets were fighting jets. What tactics did you have to learn?

Mahurin: The tactics, in terms of maneuvering, didn’t change much over World War II, except it required a lot more airspace, because the speeds were higher. The biggest problems for both sides were fuel economy and endurance. You couldn’t stay in the combat zone for a very long, because you burned up your fuel, and had to come home. But, as far as the turns and the dives and the things we see in World War I movies, with Spads and Nieuports, that kind of combat was not much different except it took a lot of airspace and went on at greater speeds.

Q: Did the early people in the Air Force fear that you couldn’t conduct dogfights at that speed?

Mahurin: People who didn’t have any jet experience came up with some half-baked ideas. A Pentagon scientist swore up and down that we would never be able to fire our guns out of the front end of a fighter jet because the airplane would run into the bullets. It wasn’t true at all, of course, because all motion is relative. But that's where technology was in the eyes of the general public at the time. Those fears were a function of ignorance.

Q: Describe what it feels like to be in the cockpit of an F-86.

Mahurin: It was more fun than anything else I’ve ever done. The F-86 was a brilliant design. Even today, it’s a very modern aircraft in terms of its engine power and so forth. It was just a delight; it didn’t have any bad habits. Unlike the MiG, creature comforts were taken into consideration. The Sabre had an air conditioning system that would produce ice if you wanted it to. It would drive you out of the cockpit with heat if you wanted. You could adjust it like a modern car. The MiG didn’t have any of that. The MiG pilot was sitting in the cockpit without any air-conditioning. Our G-suits helped us control our blood flow at high maneuvering rates, and the Russians didn’t have that either. There are more advantages -- the F-86 was a Cadillac; the MiG-15 was a Model-T Ford.

Q: What did it feel like to fly an F-86 jet fighter?

Mahurin: You had a sense of power, a sense of high performance. You didn’t think much about the airplane. It felt like a part of you. In combat, you didn’t think "I’m going to turn now, and I’m going to pull back on the stick." You just did it automatically, like moving an extension of your body. That was quite thrilling, and it was a lot of fun.

...Q: You're in the cockpit of an F-86, and you’re out after a MiG. Describe what’s going on in your mind and what you’re actually doing with your aircraft.

Mahurin: It depends on the circumstances of the combat. On several occasions, I dogfought, like World War I, with a MiG. Once we started fighting about 37,000 feet, went around and around down to the ground and back up to about 26,000, before I shot him down. So that hadn’t changed much since World Wars One and Two. It was very exciting and a lot of fun. On a couple of other occasions, we caught them when they didn’t know we were there. That was just a matter of going in and shooting down an unaware pilot. But we could outperform them with the F-86's slab tail, we could turn faster than they could, we could dive faster, and we could pull out quicker. We didn’t try to climb with them, because they could climb higher than we could. We tried to keep the combat on those elements where we had an advantage. Whenever they were gaining an advantage, we could always leave, we could always turn around and dive away.

When you talk to a pilot, especially a guy like me who has a lot of years on him, his stories get better by the moment. The next thing you know, his airplane was a dud, but due to sheer combat capability he was able to shoot down twenty enemy aircraft.

Just after the war, a North Korean pilot named Ro Kim Suk defected with a MiG-15 and landed at Kimpo airport just outside of Seoul. The MiG-15 was sent to Wright Field, and Chuck Yeager did the performance tests on it, which revealed that the F-86s was slightly faster. The Sabre had lots of combat capability that the MiG didn’t. Above all, it had the creature comforts that I talked about earlier. The MiG-15 wasn’t as good as the F-86, but all in all it was a pretty good airplane. A lot of them have survived, and once in a while, F-86s and MiGs show up at air shows, and it’s quite a sight to see them. Especially when you realize that one of them used to be an enemy.

Q: I heard that the Russians copied the British 'Nene' jet engine. So the Sabres were basically fighting against British engines.

Mahurin: The British scientist, Sir Frank Whittle, had developed a jet engine that worked on a centrifugal compressor. If you looked inside your washing machine and saw that thing rotating around, in essence that was the thing that compressed the air that went through burner chambers and then out the back end of the MiG-15's engine.

But the F-86 was powered by the GE J-47, an axial flow engine. This engine is like having a whole bunch of electric fans stuck together, pumping air in and increasing compression. That compressed air goes through the area where they have gas, and ignites the fuel, and that goes through turbine wheels on the back end, and that provides the forward thrust. Eventually, the world embraced the axial flow engine.

Q: How was the F-86 modified in the course of the Korean War?

Mahurin: There was a lot of controversy about our armament. The F-86 had six Browning fifty-caliber machine guns, which fired a bullet slightly smaller in diameter than my thumb. The MiGs used cannons, and one of the cannons was a thirty-seven millimeter, an inch-and-a-half in diameter. Many people argued that our guns were underpowered. So the Air Force put twenty-millimeter cannons on some F-86s toward the end of the war, which flew combat in Korea. But it was too late to equip all the F-86s that way. But those of us who flew F-86s were satisfied with the six fifty-caliber machine guns. It’s a tremendous amount of firepower. Until you actually see that gunfire hit a locomotive, or a tank, or a building, and see all those bullets hitting all at once, you have no idea of the power of that fifty-caliber machine gun. It was incredible.

Q: How many seconds or minutes worth of ammunition are you carrying, and what do you have to do to think through how to use that?

Mahurin: That depends on what effect you’re having on the enemy. And you can tell the damage you’re doing. If you’re not having much effect, you want to use it until you’re out of ammunition, and then you want to go home. But, if there’s a lot of enemy aircraft around, you obviously want to conserve the ammunition.

During World War II, we carried 450 rounds per gun, and the P-47s that I flew had eight of those guns. The armorers used to put five rounds of tracer ammunition before the last fifty rounds in each gun. When we saw tracers, we knew we had fifty rounds per gun left. I don’t know why we didn’t do that in Korea. Very few people ran out of ammunition. I did several times, but mostly because I was shooting up ground targets. When you fire three seconds worth of those fifty-caliber bullets, it’s an awful lot of bullets, it’s an awful lot of power. If you’re in the right position, you really don’t need any more. ...

Read the full interview with Bud Mahurin

Boots Blesse 1997 Interview for SECRETS OF WAR

Q: Compare the MiG-15 to the F-86 Sabre.

Blesse: Air-to-air fight was like a game. You had to know the rules. You had to know what you could do and what he could do. We had pretty good information on the MiG. It was a point defense airplane, smaller and lighter than the Sabre; it didn’t carry as much fuel. Consequently it could out-climb us at any altitude and had more than double our rate of climb above 25,000 feet. It could outrun us at any altitude. So a MiG pilot had a lot to work with. But if you’re an F-86 pilot you had a couple of things you could try with this gopher, and one of them is turn. You don’t want to try to outclimb him if he’s behind you. So you measure these things into the fact. When you first sight him you hope to get an advantage by getting in his rear quarter. You know that he’s immediately gonna turn into you, and you need to know how to respond. You close in as close as you can. With fifty caliber machine guns you gotta get within 1200 feet to do any good. Most of the airplanes I shot down were within 400 to 1000 feet.

It’s a matter of training and practice. What if he turns into you and gets too close, and you can't make that turn? You gotta know what to do. You gotta know that the nose goes up, and let him come down, and then when you come around you’ll still be behind him. If you try to stay on his plane, you’re gonna stall your aircraft. Pretty soon you’re in trouble because he’s gonna reverse his turn, and you’re gonna be on the outside going away from him, and you’re going to have him behind you. That's what we tried to teach. We tried to make sure that our people didn’t unnecessarily expose themselves to a disadvantageous position in combat.

Q: Describe the different models of the F-86.

Blesse: In December 1950, the USAF began flying the Sabre

model designation F-86A in Korea. It had manual cable controls, but it

was the only swept wing jet fighter available, and they elected to send

it to Korea where it was combat tested. They were still flying the "A"

when I got there, in April of 1952. My first sixty missions I flew in

an A-model.

The "A" did not have the hydraulic control system that came with the F-86 E-10, which was the second model. I flew the rest of my 100 missions in the E-10. I volunteered for twenty-five more and flew those in the F-86 E-10. In June we began getting a Canadian E-10 which had hydraulics to power the flaps, ailerons, and elevators. Moving the flying surfaces by hydraulics was a lot better than by cable because you could roll the aircraft over at high altitudes, and still do something with it. If you rolled the "A" over at 35,000 feet it just dived like an arrow until you got down around 18,000 feet where the air was a little thicker and you could control it then. Everything was done with hydraulics in the E-10, which cost more weight. While it had the same engine as the "A," it was slower . But the E-10 was good, and I flew it for the rest of my time in Korea.

After the E-10, after I left, they got the "F" model. From January to June 1953, our guys flew the "F," which had a "six three" slat in it. The slat was three inches thick and came down six inches at slow speeds. That gave you much better turning capability. The E-10 had a six five slat, which was quite thick, and although it did some good, it wasn’t nearly as good a turning airplane as the "F" model with its six three. Also the "F" had a modified engine with 600 pounds more thrust. That allowed you to turn tighter, and it also allowed you to climb better. That was very important in a fight. A third thing was the twenty millimeter guns. At the end of the war some of the "F" models came over equipped with twenty millimeter guns. These allowed you to fire at a MiG from a couple thousand feet and still get some significant damage.

And that’s the way they finished up the war -- with the bigger engine, the six three slats in the "F, and the twenty millimeter gun. The slat, the engine, and the gun. Those were the three primary things that helped increase our kill ratio by the end of the war. But we had about ten and to one during the time I was there. And the ratio got even better after these airplanes got into the theater.

Looking back on my tour I’m very grateful that I was over there at that time. I’m lucky to have scored as many kills as I did without getting in any serious trouble. Only two guys, Davis and I, got ten or more kills in the old airplanes. All the other people that got ten were flying late in the war when there was more activity and better equipment. But I would have liked to have been there six months later.

Sperry A-1C gunsight

We used a marvelous gun sight, the Sperry A-1C radar gunsight. It had a range limiter on it, which you could set to 1000, 1200, or 1600 feet. The earlier gunsights had a pipper in them and if you didn’t have this range limiter to set, the pipper would go off the screen when you turned sharply, and it wouldn’t display, because you needed more lead than it could give you. Until you backed off on the "G’s," the pipper wouldn't come back. Well you can’t do that in a fight. So that wasn’t very useful to us. But when they developed this range limiter, you’d set it on 1200 feet, for example, and that dot would stay right there. It would only drift off maybe a quarter or half an inch. You’d just continue to maneuver until you got close enough. The range limiter would activate when you crossed 1200 feet. From then on you were getting actual lead to your target. So you waited for that sign on the circle that was around the dot. When you got that, you were getting good lead. You'd get the pipper on him and go after him. ...

Read the full interview with Boots Blesse

F-86 Sabre jet

F-86 Sabre jet