Paul Tibbets and the Enola Gay

Led mission that dropped first atomic bomb on Hiroshima

By Stephen Sherman, Nov. 2002. Updated June 29, 2011.

The B-29 Superfortress, Enola Gay, rumbled down the the runway at Tinian, the forward American airbase in the Marianas, as close as the giant Boeing bombers could get to Japan's Home Islands. Heavily laden with the world's first operational atomic bomb, the B-29 shuddered and trembled as its four 2,000 horsepower Wright Cyclones roared. Its pilot, Paul Tibbets, thought briefly of the recent B-29 crashes on Tinian, and then focused on his mission.

"Dimples Eight Two to North Tinian Tower. Ready for takeoff on Runway Able," he radioed to the tower. The Enola Gay picked up speed, 75MPH, 100, then 125. Tibbets held the plane on the runway until it reached 155 MPH, then eased back on the yoke. Near the end of the 8500 foot runway, the B-29 lifted easily and steadily into the air. Tibbets checked his watch, which showed 2:45AM, the morning of August 6, 1945. In ten minutes they were over Saipan, at an altitude of 4,700 feet. In the pleasantly warm tropical night, during the thirteen hour flight, Tibbets and the other crewmen dozed off and on. It's possible that he thought back to another summer day, in 1927, over Miami's Hialeah racetrack.

Youth

Paul Tibbets was born , son of Enola Gay and Paul Warfield Tibbets in Quincy, Illinois. Attracted by the land boom, the Tibbets family moved to Florida when Paul was nine. On that memorable summer day, a barnstorming pilot, Doug Davis, let the twelve-year old Paul ride in his Waco 9 airplane and toss Baby Ruth candy bars to the crowds at Hialeah racetrack and Miami Beach. Tibbets always traced his interest in aviation to that day. The next year, 1928, he entered Western Military Academy (WMA), where Butch O'Hare attended at the same time. Here he learned many of the rituals of military life, such as hazing and room inspections where the inspector was likely to rub a white glove across the sole of his foot and issue a demerit for "dirty floors."

He enrolled in the University of Florida at Gainesville in 1933, more or less to follow his family's plan for him to pursue a medical career. With this goal still in mind, he transferred to University of Cincinnati after his sophomore year, where he continued to take flying lessons. After some major soul-searching, and a difficult conversation with his father, he decided that his heart was not in medicine, but rather in aviation.

Following this dream, he joined the U.S. Army Air Corps, and reported to Randolph Field in 1937. From his years at WMA, he was familiar with hazing, inspections, and other demands of military routine. He trained on PT-3's and BT-9's, the standard trainers of the day. He graduated first in his class, and unlike most of the other top pilots, he did not elect Pursuit, but rather multi-engine Observation duty, because he thought Observation would offer him more independence. From 1938 through 1940, while at Fort Benning, he flew O-46 and O-47 observation planes and B-10 bombers.

Here he met George Patton, then a Lieutenant Colonel, and destined to become the world-famous tank General in World War Two. While Tibbets was a lowly Second Lieutenant, they went skeet shooting together. Patton was a fierce competitor and "screamed in fury" at the few quarters he lost competing against Tibbets.

Tibbets learned a whole new approach to flying in 1941, when he began to fly the Army's new attack bomber, the A-20. While earlier bombers has sought refuge in altitude, the development of radar and the A-20's mission, forced the A-20 pilots to fly on the deck, barely 100 feet off the ground. He was flying over the skies of Georgia, listening to a commercial radio station, when he heard the news of the attack on Pearl Harbor. The United States was at war! Amidst the rapidly changing priorities of early 1942, Tibbets (now a Captain) found himself in a squadron of B-18's destined for anti-submarine duty over the Atlantic. He soon transferred to the four-engine B-17 Flying Fortress, as commander of the 40th Squadron of the 97th Bomb Group (Heavy).

Flying B-17s over Europe

In the summer of 1942, he and the 97th flew their B-17s to the war: taking off from Bangor, Maine, stopping in Labrador, Greenland, and Iceland en route to their new base at Polebrook. The 97th BG served as the model for the famous movie Twelve O'Clock High; Tibbets, as a Major left in charge of the Group, was even depicted in the movie. Armstrong, the new CO of the 97th, appointed Tibbets his XO.

The first mission was scheduled for August 9, but a week of rain delayed it and increased the already considerable tension of the air crews.

On Aug. 17, 1942, he flew the B-17 Butcher Shop in the first daylight bombing raid by an American squadron over German-occupied Europe. On that morning, General Spaatz and various British brass, watched the take-off. 18 bombers flew that mission, the first of over 300,000 bomber sorties that the Eighth Air Force would make. Brigadier General Ira Eaker, head of VIII Bomber Command, also flew this mission in the Yankee Doodle and received official credit for "leading" it. They lifted off just after noon, climbed to 23,000 feet, and headed for Rouen and Buddicum, strongly escorted by RAF Spitfires. Three planes carried 1,100-pounds intended for the marshaling yards at Rouen; another nine planes carried 600-pound bombs for the repair shops at Buddicum. In mileage, it was a short mission. The bombers hit train repair shops near Rouen, and all returned safely.

For the next few months, they flew frequent missions, and continued training intensively in England, practicing gunnery over the Wash. Tibbets. Remembering his days cleaning the cannon at WMA, insisted that his crews disassemble their machine guns, wash them thoroughly, and then lightly rub every part of the gun with gun oil, thus reducing the risk of the guns freezing or jamming at 20,000 feet.

In late 1942, as the Americans prepared for Operation "Torch," the invasion of North Africa, Tibbets was called on to fly General Mark Clark on a secret mission to meet with the French commander in Algiers. Flying the Red Gremlin, he flew Gen. Clark to Gibraltar, where a submarine picked the general up and brought him to Algeria. Clark's mission was successful; numerous French units cooperated with the Allied landing forces. Apparently the brass were impressed with Tibbets' general-ferrying skills; on Nov. 5, her flew General Eisenhower from England to Gibralter. With the plane crowded with staff officers, Ike sat on a two-by-four hastily installed in the cockpit, so he could get a pilot's eye view of the flight, which went off smoothly.

North Africa

After the Allies established themselves in Algeria, Tibbets' B-17 group was based first at Maison Blanche (outside Algiers), then at Tafaraoui ("deep and gooey"), and then at Biskra. In early 1943, he was transferred to the 12th Air Force, under General Jimmy Doolittle, where they wrestled with the challenges of the B-26 Marauder, a good plane, but one that was "a handful" for many pilots. It was during this time that Tibbets first crossed paths (and swords) with Lauris Norstad, a politically adept officer who, in the post-war years, stymied Tibbets' Air Force career.The B-29 Superfortress

In July, 1943, he reported to "Boeing Wichita," one of the four plants devoted to the new bomber. Originally drawn up as early as 1940, the B-29 was an innovative aircraft: a fire control system that permitted one gunner to operate five pair of machine guns, a pneumatic bomb bay door, and completely pressurized crew compartments (connected by a crawl-through tube), tricycle landing gear. It was larger, faster, could fly higher & farther, and carried a larger bombload than a B-17. At Grand Island, Nebraska, he started a school to train B-29 flight instructors, where he connected with Frank Armstrong, his old commander at Polebrook, Among other things, they found that removing some of the heavy machine guns and ammo made a big difference in the Superforts' performance.In Sept. 1944, he reported to Colorado Springs for a top secret assignment - to organize bombardment group to deliver the atomic bomb. Following a detailed personal interview, he was introduced to General Uzal Ent and Professor Norman Ramsey, who explained the project to him. Tibbets force, the 509th Composite Group, included 15 B-29's and 1,800 men. The 509th settled on Wendover, Utah as their base. Due to its remote location, it was ideal for security. From his old B-17 crew in Europe, he selected Tom Ferebee (bombardier), Sgt. George Caron (tail gunner), Dutch Van Kirk (navigator), and Sgt. Wyatt Duzenberry (flight engineer). These men were assigned to Tibbets' airplane. Bob Lewis flew as co-pilot. As Tibbets could get any men and any planes he needed, the 509th quickly filled out, and the entire organization was complete by Dec. 1944.

The primary challenge would be to drop the atomic bomb, without the shockwave destroying the B-29. The scientists estimated that a B-29 could survive the shockwave at a distance of eight miles. Flying at 31,000 feet, the B-29 would already be six miles in the air. To gain the extra distance, Tibbetts determined that a sharp 155 degree turn would be the best maneuver. In less than 2 minutes, the B-29 would reverse it direction and fly five miles; Another critical concern was accuracy; using the Norden bombsight, the bombardiers would have to put the bomb within 200 feet of the aiming point. Another challenge was to navigate over water and land; the transition could be disorienting. So Tibbets and his men trained for this navigation in Cuba. The Cuba training exercise gave him the opportunity to fly his mother, Enola Gay Tibbets, in a C-54 transport plane to visit him, surviving and even enjoying a turbulent flight, complete with St. Elmo's Fire.

Tinian - 509th Composite Group

By May, 1945, Tibbets and the 509th had moved out to the Pacific, to the island of Tinian in the Marianas. As it was shaped something like the island of Manhattan, the Army engineers named the base facilities with names like Broadway and Forty-second Street. Tibbets' group bivouacked in the "Columbia University district." Tinian was ideal; its 8,500 foot runways were among the longest in the world at the time. Tibbets ran into various confrontations, on issues from maintenance to training, stemming in part from the secrecy of the operations. He flew back and forth to the States three times between May and July, but missed the first atomic test at Alamogordo because he had to return to Tinian to persuade General Curtis LeMay not to switch the atomic mission to another outfit.On July 26th, the cruiser Indianapolis dropped anchor off Tinian and unloaded a 15-foot wooden crate. Inside was the atomic bomb, complete except for a second slug of uranium that a B-29 later delivered. Having delivered its load without incident, Indianapolis moved on toward the Philippines. Though intelligence reports assured Captain Charles McVay that the route from Guam to Leyte was safe, there were Japanese submarines active in the area. Four days after departing Tinian, Indianapolis was sunk by a Japanese submarine.

The Mission

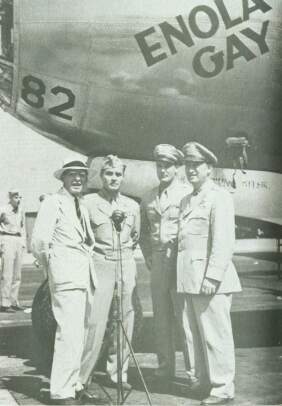

By early August, 1945, plans for the first atomic mission were set. Seven Boeing Superfortresses would take part, including the primary, a standby, a photo plane, one with scientific instruments to measure the blast, and three others that would scout ahead. Bombing would be visual, rather than by radar. Possible target cities included Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata, and Nagasaki. Until this time, Tibbets' own plane had been simply number 82, when he decided to name it Enola Gay, after his confidence-building and loving mother.

Crew

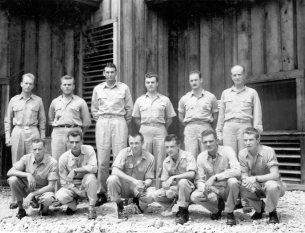

Twelve men crewed the plane:

- Capt. Robert Lewis - copilot

- Maj. Thomas Ferebee - bombardier

- Capt. Theodore Van Kirk - navigator

- Lt. Jacob Beser - radar countermeasures

- Capt. William "Deak" Parsons - weaponeer

- 2nd Lt. Maurice Jeppson - assistant weaponeer

- Sgt. Joe Stiborik - radar

- Staff Sgt. George Caron - tail gunner

- Sgt. Robert Shumard - asst. flight engineer

- Pfc. Richard Nelson - radio

- Tech Sgt. Wayne Duzenberry - flight engineer

Shown in photo above. Standing: Lt. Jeppson, Capt. Lewis, Gen. Davies, Col. Tibbets, Maj. Ferebee, Capt. Parsons. Kneeling: S/Sgt Duzenbury, Sgt Stiborik, Maj. Van Kirk, S/Sgt Caron, Sgt Shumard, PFC Nelson. (Gen. Davies, the Commanding Officer, was not part of the flight crew.)

They got the word on Sunday morning, August 5. Conditions were go, and the next day would be the day. At the last minute, it was decided to complete the final assembly of the bomb in flight, thus eliminating the risk of it exploding if Enola Gay crashed on take-off. Navy Captain Deak Parsons, who had earlier opposed this idea, now suggested it, and persuaded the team that he could perform the difficult assembly in the cramped bomb bay of the B-29.

They loaded the bomb into the Enola Gay that afternoon. "Little Boy" was 12 feet long and 28 inches in diameter - bigger than any bomb Tibbetts had ever seen. Its explosive power equalled 20,000 tons of TNT; or roughly as much as two thousand Superfortresses could carry - all in a single bomb that weighed about 9,000 pounds. Deak Parsons practiced the delicate arming process. That night the crew was briefed, for the first time, on the nature of their weapon - an atomic bomb.

Flight of the Enola Gay

Chuck Sweeney, with the scientific instruments in the Great Artiste, would follow Tibbets' closely, duplicating his hairpin turn. George Marquardt's photo plane would stay far behind, out of range of the shock wave. The three weather planes, Claude Etherley's Strait Flush, John Wilson's Jabbitt III, and Ralph Taylor's Full House, would take off an hour ahead, to scout out the designated target cities. Every crewman carried a standard service pistol; Tibbets carried enough cyanide capsules for all. They started engines at 2:30 AM on the morning of August 6, 1945. Three hours after takeoff, they flew over Iwo Jima at dawn, where 5,500 Americans and 25,000 Japanese had died, so that the USAAF could use Iwo as an emergency landing field. They adjusted course and headed northwest. At 7:30, Deak Parsons completed his adjustments; the atomic bomb was live. They climbed slowly to their bombing altitude of 30,700 feet.

At 8:30 they received the coded message from Etherley's Strait Flush, flying over Hiroshima, "Y-3, Q-3, B-2, C-1." The message meant that cloud cover over Hiroshima, the primary target, was less than three-tenths. Tibbets gave the word to his crew, "It's Hiroshima." As they reached the coastline of Japan, no interceptors challenged them; the Japanese had become indifferent to small groups of B-29s. They crossed Shikoku and the Iyo Sea.

Hiroshima

They looked down at the city below. The other crewmen verified that it was indeed Hiroshima. They spotted the Initial Point, or I.P. They turned and headed almost due west. Tom Ferebee peered into his Norden bombsight, and cranked in the information to correct for the south wind. Tibbets reminded the crew to put on their heavy dark Polaroid goggles, to shield their eyes from the blinding blast. It had been calculated to have the intensity of ten suns. They easily spotted the distinctive T-shaped bridge that was their primary. 90 seconds before drop, he turned the controls over to Tom Ferebee, the bombardier. At 9:15AM (8:15 Hiroshima time), they dropped "Little Boy" and made a 155 degree diving turn to the right. Unable to fly the plane with the dark goggles, they shoved them aside.

The Atomic Bomb

43 seconds later, a tingling in Tibbets' teeth told him of the Hiroshima explosion: the bomb's radioactive forces interacting with his fillings. The bomb exploded at 1890 feet above the ground. Bob Caron, the tail gunner was the only crew member to see the fireball. Even wearing the goggles, he thought he was blinded. The plane raced away, while the shockwave from the explosion raced toward them at 1,100 feet per second. When the shockwave hit, it felt like a near-miss from flak. The mushroom cloud boiled up, 45,000 feet high, three miles above them, and it was still rising. They flew away, shocked and horrified at the sight below. The city had completely disappeared under a blanket of smoke and fire. They radioed back to headquarters that the primary target had been bombed visually with good results.

The mushroom cloud over Hiroshima was visible for an hour and a half as they flew southward back to Tinian. The crew talked about the effect of the atomic bomb on the war. They thought that perhaps the Japs would "throw in the sponge" even before they landed. Twelve hours after they had taken off, Tibbets and the crew of the Enola Gay touched down, to be greeted by all the military brass that could be mustered: General Carl Spaatz, commander of the Strategic Air Force; General Nathan Twining, chief of the Marianas Air Force; General Thomas F. Farrell and Rear Admiral W.R.E. Purnell, both with the atomic development project; and General John Davies, 313th Wing Commander. Spaatz pinned a Distinguished Service Cross on Tibbets as he descended from the plane.

After the welcoming formalities, they were debriefed and given a quick medical checkup. The interviewers were skeptical of their accounts of the blast. The news of the atomic bomb was promptly announced to the world. The Japanese were given an ultimatum, to accept the Potsdam call for unconditional surrender, or face further atomic attacks. Three days later, Chuck Sweeney, in Bock's Car, dropped the second atomic bomb on Nagasaki.